|

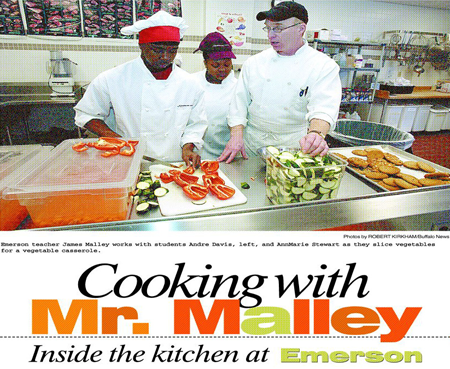

| COOKING WITH MR. MALLEY Inside the kitchen at Emerson Buffalo News Wednesday, March 24, 2004 Section: NEXT Page: N6 Thwack, thwack, thwack went the knife as Monique Rogers, 17, applied it -- thwack! -- and sliced up one stalk of celery -- thwack! -- after another -- thwack! She was mad. Thwack. She doesn't like Buffalo's hospitality-learn-to-cook high school. Thwack, thwack, thwack."I personally did not choose this school," she explained from her place at the stainless steel counter of the Emerson School of Hospitality on West Chippewa. "I came from McKinley. I really, personally, don't like coming here." Since her vocational-program transfer this year from McKinley High School, where she left schoolmates she now misses, there is only one thing she admits to liking along with everyone else: The restaurant-fare-preparing class taught by red-haired, loud Chef Instructor James Malley, who likes to philosophize about the connection between cooking and life. To his workers, at what may be the only high-school-run eatery in the country, he offers lessons in a direct way: "There's nothing wrong with learning to cook at 16, 17 years old. It's a nice little tool to have in your pocket," he declared as he patrolled the kitchen. And, he teaches indirectly, too -- in way that can dawn on his students gradually. As they thwack at celery stalks, or stir flour into melted butter for soup that will go on the Emerson Commons menu, they sometimes discover good things about themselves and about life, without Malley spelling it out for them exactly. During one recent pre-lunch kitchen rush, Malley used his direct and indirect methods as his proteges, in white chef hats and jackets, wielded knives and whisks to prepare quiche, fish, pizzas, roasts and vegetable sautees. He stopped to correct one mushroom-slicer. "Not like this," he said, adjusting a young man's grip to keep fingers away from the blade, "like this." Malley, who sometimes gets so worked up about food that he starts yelling, cheers up senior Edgardo Mercado, 17. As he stood cutting carrots for the mirepoix vegetable mix used for stock, Edgardo said Malley's yells keep people focused. He makes the school day interesting and more fun than the more ordinary animal science class, which Edgardo dislikes. Malley overheard this and interjected. Such "dull" science does matter. "You're going to get a lot of that thrown at you in college," he said. "You'll be ahead of the game. Don't look at things so short-term." Edgardo grinned. "He keeps the kitchen alive," he said. He's thinking of going to college for computer programming, or hospitality. For now, he has a job washing dishes and learning to cook at Main Street's Lake Effect Diner, which Malley helped him secure by giving a good recommendation. "He really buckled down. I'm really proud of him," Malley said, walking off past the windows. There is a clear view of people on the sidewalk hurrying toward the door to Emerson Commons, just beyond the kitchen. Soon it would be serving some soup made with Rogers' celery pieces, piled up on the cutting board. When a handful gathered, she dropped it -- plunk! -- into a bowl of water. The bits, which had absorbed her frustration, bobbed cheerfully to the surface. While she is annoyed, in part, because Emerson was her only option when a medical-related vocational program she wanted was full, it is Malley who notices when she's not doing well. "He'll be like, 'You look messed up today,' and I'm like, 'I know,''" she said. She appreciates his admonishments. "I like Mr. Malley because his class is so demanding," she said. "When you're doing something wrong, it seems like he's playing with you, but he's really serious." He taught her how to make a shrimp dish with pasta, scallops and cooking wine, which she has now made three times. "It came out great," she said. "I can't cook, but he taught me how to do that. When I get my own house, I'm going to make it." She'd never sauteed vegetables before. Now Malley compliments her on how well she shakes the pan. "He'll pass me when I'm doing it and he'll be like, 'Great job, great job,'" she said, continuing to thwack the celery into a pile on the cutting board. The work in this two-hour class had made her feel better. "When I leave here," she said, "I'm cooled down." For now junior Jessica Dabb had Malley's attention. He'd heard her claim she didn't know how to make seafood chowder. "You know what you're doing. You've done it before," he said, walking beside her. "Give me your hand. Let's talk, OK? I'm going to tell you what to do again." When she was settled, he roamed the kitchen, talking about how he is proud that his students get jobs easily -- at Wegman's, Rich Products, the Rue Franklin restaurant. Employers like that Emerson students already have professional work experience. Learning to cook, Malley said, does not limit a person's future. It can be a step, a way to pay the bills through college. Or, the beginning of a career in the hospitality industry of hotels and restaurants, which is one of the world's largest. The industry is a secure way to earn a living because, said Malley, the world will always need people who know how stand in a kitchen and cook. These days kids get interested in the work because they watch TV cooking shows that make roasting a chicken look cool and glamorous. So as the school's old vocational trades of cabinet making and welding fell away, demand for Emerson's hospitality program increased. The original Emerson Vocational High School opened in 1926 on Sycamore Street and closed in 1999; the new Emerson opened three years ago. Next year enrollment will go up from 285 to 400. An addition behind the restaurant will open with a fitness room, an art room with refrigerators for table flower arrangements, cooking demonstration stoves and plain classrooms for studying the English and math requirements needed to pass the state exams. About 85 percent of graduates go on to some kind of post-high-school education, which Malley loudly encourages. "If you have a college degree, you can always build on that as a ladder. That was the key with me. If you learn to cook, you can get that," he said. "Life is a continual learning experience." To illustrate this point, Malley filled his kitchen office wall with records of his achievements, which include a diploma for the master's degree in education he earned at 37. He likes students to know the bachelor's degree he earned as a young man let him build toward graduate school as an older adult. Before that he was a certified executive chef who had spent 20 years cooking at the now-closed Greek restaurant Yianni's, a country club, Canisius College, and finally, Sisters Hospital. A few wall plaques commemorate his eight-year teaching career: The Winterfest ones represent the three years he and his students competed against regular restaurants in the Police Athletic League's annual chili cookoff. After losing each time with the same vegetarian chili, this February Malley decided to use a meaty recipe he'd picked up at the hospital. "It's so simple, it's ridiculous," he said. He'd assigned senior Andrae Davis to make a giant kettleful for the judges and the crowd. For two days of class, the solemn 17-year-old worked by himself. First he assembled the ingredients: 30 pounds ground beef, three onions, two big number 10 cans of kidney beans, diced tomatoes and tomato puree, one and a half cups chili powder, 3/4 cup of paprika, three tablespoons cumin, three green peppers, two quarts beef stock and a quart of chopped celery. The next day Andrae simmered the meat, drained the grease and added the rest. On the following Winterfest Saturday, he couldn't find a ride. So it wasn't until school the next Monday that he found out his chili beat the professionals from the Park Lane, the Wellington Pub, the Lake Effect Diner, Cozumel and Cole's. "The fact that it won was even better because I knew I did it all by myself," he said. "I never made anything like that before," he said. "It gives me confidence that maybe I could prepare other things." Davis has one regret about the chili. He wishes now he'd tasted it.

|