|

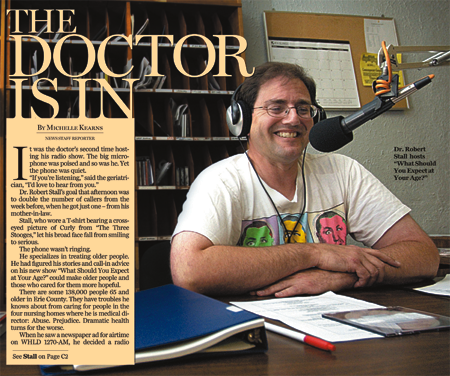

| THE DOCTOR IS IN A Buffalo geriatrician has taken to the airwaves to expand his grass-roots effort to improve the quality of life for the aging population BUFFALO NEWS Tuesday, July 20, 2004 Section: LIFESTYLES Page: C1 It was the doctor's second time hosting his radio show. The big microphone was poised and so was he. Yet the phone was quiet. "If you're listening," said the geriatrician, "I'd love to hear from you. "Dr. Robert Stall's goal that afternoon was to double the number of callers from the week before, when he got just one -- from his mother-in-law. Stall, who wore a T-shirt bearing a cross-eyed picture of Curly from "The Three Stooges," let his broad face fall from smiling to serious. The phone wasn't ringing. He specializes in treating older people. He had figured his stories and call-in advice on his new show "What Should You Expect at Your Age?" could make older people and those who cared for them more hopeful. There are some 138,000 people 65 and older in Erie County. They have troubles he knows about from caring for people in the four nursing homes where he is medical director: Abuse. Prejudice. Dramatic health turns for the worse. When he saw a newspaper ad for airtime on WHLD 1270-AM, he decided a radio show just might work. Already on the air that particular afternoon, he'd told his joke about how his patients are the biggest carriers of "AIDS." Hearing aids. Walking aids. And he'd played his recorded stories. The woman in her 90s playing songs on bells. Local actor and director Saul Elkin read Shakespeare's seven ages of man poem. Stall's 10-year-old daughter talked about what she loved about her grandparents -- going to the beauty shop, home-cooked chicken, trips to Florida. He gave the number again -- 855-6848. Still, nothing. Stall, 47, who is also an assistant professor of medicine at the University at Buffalo, has tried not to get too discouraged as he gets started. He is an optimist about this crowd. He doesn't like to say "old," because it's too negative. He wants to make people feel healthier and less neglected as they get older. He knows doctors sometimes don't have time for long conversations to figure out what's wrong with patients of any age. He can't take on many more himself, so he has developed a solution he's calling grass-roots geriatrics. He wants his effort, which includes his broadcasts, to show people that they shouldn't expect to feel bad just because they're old. "There is always something that can help!" Stall wrote in an announcement. Twice he has worked with Lions Club members and other health care workers to organize health fairs in senior housing units. Since doctors have so little time, Stall has people identify problems using an assessment form he developed. It asks older people and their caregivers about chronic pain, dark moods, incontinence, night waking for bathroom trips. A doctor can then look at the answers and tackle the problems. Radio, Stall thought, would be another way to get the word out. Some troubles are so easily fixed, such as people taking too much of too many different kinds of medicine. One over-the-counter pain reliever and sleeping aid makes patients anxious and psychotic. A friend's brother was so depressed -- until Stall advised he stop the pills -- that the friend was afraid to let his brother return home to Florida. During Stall's residency at Veterans Affairs Medical Center, a frail, thin man in his 90s arrived unconscious and was thought to have dementia. Stall found pneumonia, which was improved with an IV and antibiotics. Not long after, the man went home and gardened. Another time, Stall gave a nursing home checkup to a woman who had not spoken in a year. He removed an inch-thick earwax plug from each ear. She replied softly, "I'm OK," when he asked how she was. "To be totally isolated by deafness because of earwax was a shame," Stall said. He is lenient about diets. A nursing home resident thrives on takeout fried chicken for dinner every night, and Stall approves. "It makes him happy," he said. Geriatricians, he said, are trained to be most interested in getting people to enjoy life and ease pain. Definitively curing disease is not a priority. "Truthfully," he said, "I don't think geriatrics should be a specialty. I'd love to be put out of business, but I don't think it's going to happen." Fewer and fewer doctors choose it as a specialty: Certification records show a drop from 1,254 in 1991 to about 200 or 300 between 1995 and 2001. Stall, who is among 40 or so local geriatricians, was drawn to it because he had been lucky with his grandparents. All four of his grandparents were alive for most of his life. "It's hard to believe they're not here to talk to and hug," he said. As the second half of the show -- the call-in half -- came to a close in the small WHLD studio on Delaware Avenue, Stall was tired. He'd been up until 3 in the morning editing his interviews. "The call lines are open. Come on. Let's get on the phone here," he said. "Now, I don't hear any phone calls yet." The phone rang. Wonderful. A woman wanted the definition of a term that describes a precancerous condition of the esophagus. And that was it. Just one call -- from his wife's cousin. For the next 15 minutes, Stall tried to explain how his self-assessment test worked by reading aloud from its questions. "What is the one thing that you do that you enjoy the most?" "What bothers you the most?" Stall wondered if he was doing the right thing on the radio. Pop psychologist doctors had shows, so why not someone for older folks? His parents thought he should be syndicated already. But was anybody else out there interested? Was anyone listening? He could easily think of a year's worth of programming. He'd like to interview Walter Gretzky. He knows the father of Canadian hockey star Wayne Gretzky just had a stroke. He wants to talk to a classics professor about Cicero's writings about aging. He intends to play the Beatles' song "Help!" for a show for caregivers of people with dementia. In fact, he could use some help himself. He was doing this all on his own. It's hard to find like-minded people to try crazy things. This was like going out naked into the world. "I'm waiting," he said to the microphone. "855-6848. I'm shuffling my papers again. I want you to call in next week." Next time he planned a show with stories of people's embarrassing moments. That way, he thought, he could better begin to explain how feeling embarrassed a lot is part of getting older. People forget names or can't hear properly. More and more, he would say, things going wrong are just a regular part of everyday life. Find out more and listen to the radio program online at www.whatshouldyouexpect.com. |