|

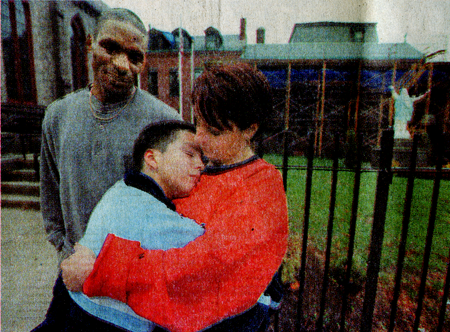

| FOR ONE FAMILY, NO HOME = TIGHTER UNION Cast on the streets, a family finds simple joys, and its footing BOSTON GLOBE Sunday, December 8, 2002 Section: City Weekly, Page 1 A row of squirrels running up and down a tree in Boston Common was one of the most beautiful things Lisa Bernard had ever seen. She, her husband, and her son stood in the park, transfixed. There was still time before curfew, so they stayed an extra hour and watched. Before they left for the T, they marveled as squirrels took peanuts from a man and a little girl. Then the family of three rode back to East Boston. From the Maverick stop they turned a corner to Havre Street and the statue of the Virgin Mary reaching out her arms on the lawn at the Most Holy Redeemer Church. Inside the old convent next door, their three beds were crammed into a small room at the shelter for homeless families. Bernard had gone to the Common to take a $2 ride on one of the swan boats she remembered from her childhood. The squirrels they saw afterward were a surprise, just as the whole homeless thing was a surprise - surprising that it happened and surprising that there was good in it. Last spring, when the eviction notice arrived at their Lowell apartment, the good part wasn't obvious. They couldn't pay rent after Bernard's worker's compensation checks were canceled when a doctor decided the ruptured disks in her back were from an old injury and not one her last employer, a pizzeria, should pay for. Her husband, Daniel Osgood, had just started a landscaping business, but at that time of year he wasn't getting much work. So they left behind most everything: the kitchen she'd painted antique white and applied with border paper of antique pitchers and fruit; clothes; her son Carlos's dresser and bed; pictures on the wall; lamps; the TV; the VCR; the entertainment center cabinet; and the bed where she would sit among her pillows watching football. "If I had time to put stuff in storage, I would have," she said. After the local welfare office said she couldn't get help because of her husband's job, she took what she could carry, including a plastic tote of keepsakes with baby shoes, wedding pictures, and an artificial valentine rose from her husband. Once they got to Osgood's mother's place in Jamaica Plain, they obtained welfare, and then it was boring. In the state-funded hotel rooms in Braintree and Revere, day after day went by with nothing to do. Osgood quit landscaping so he wouldn't make too much money and lose the benefits. With fewer distractions and close quarters, they tried to make being homeless into a vacation. At home in Lowell, Osgood had been thinking the family was drifting apart, each so busy with work or school. So together they used food stamps to buy juice boxes to take to the carnival, so they wouldn't spend their money on high-priced fair food and Carlos could go on most every ride. They made a photo album with pictures of the deck at the beachside motel and of Carlos grinning the night he got back from a scholarship-paid summer camp, his first. Toward summer's end, when they got the room at the Crossroads Family Shelter, Bernard was noticing a change in her son. Carlos is a wiser boy now, she said. Maybe it helped that her husband, without the job that once took 60 to 70 hours a week, had more time to take walks with him. He has become calmer and less wild. This is not easy in the shelter, which is crowded with 12 families, Spanish-speaking mothers mostly, including some 25 children from 3 months to 17 years old, running, yelling, crying, and watching one of the two televisions in the rooms with big couches. The only other place to sit is at one of the white tables in the white linoleum kitchen, with its rose patterned window swags and cabinets with padlocks, where she keeps some of her family's food cache - brownie mix, cheese crackers, coffee, tea, chocolate frosting, and sugar-free chocolate syrup. The shelter's strict rules seem designed to make life spare - no drinking, not even a beer with a friend, no staying elsewhere overnight without permission, no eating or TV in the room, inside by 9:30 p.m. To keep things interesting, they signed up for all the outings that the shelter coordinator planned. The harbor cruise and visits to the aquarium, science museum, and Celtics games. After a while, the strangers living around her began to feel like family, and being homeless seemed good in a lot of ways. One woman's children wanted Bernard to sit at their table for the dinners of chicken and rice or spaghetti that people take turns making. Bernard, after coaxing from the housing worker, began saving money even though it was hard and there wasn't much left of the $164 biweekly welfare check after food and new jackets for herself and her son. She tried to stop frivolous spending. She didn't need to buy another toy for Jordan, her 2-year-old grandson, who now didn't seem to recognize her as easily as he did when she lived near him in Lowell. Her son didn't need another PlayStation game, even though all the other children have them and the pressure to have what everyone else has is a powerful force. "I've got a couple games I'm satisfied with," Carlos said, with a grown-up kind of seriousness. He said he has learned there are lots of things people can easily do without. "Like measuring cups," he said. Now when he makes brownies from a mix, he can do the oil, milk, and water measurements with any cup, knowing by heart how much to put in. His mother calls her son, who celebrated his 14th birthday in the shelter, more compassionate these days. In the subway, he's given change to performers, thinking they were working hard to support their families. "He gets to see reality. The world isn't in poverty, but the world isn't well off," she said. "It's taught my son to care." When Carlos started high school in September, he joined the junior ROTC, competing with the drill team. His grades and marks for behavior and attitude were good - As and Cs - with the exception of algebra, which he had warned his mother he would fail because he needed extra help. "Ma, for the first year in high school, I did pretty good," he said, and Bernard told him she's seen him do better, but she also said she is proud of him. Now after three months, they crave their own private space, but they've made their room homelike. "I want to leave, but I don't want to leave," Bernard said. Over the light switch, she hung a souvenir tile of a cow from her daughter's trip to Portugal to visit her boyfriend's family. Over their beds are fake fluorescent-green-tinged spider webs with plastic spiders, decorations from the shelter's Halloween party. On top of the metal closet there are boxes for two small lamps, ready for the new apartment they'll move into in Lowell in December. Last month her husband found a good job at a printing plant, refusing the $12-an-hour rate they offered, taking $8 instead so they could stay qualified for the Section 8 government rent discount. One afternoon, Bernard screamed with happiness when news of it arrived in the mail. "Thank you God," Osgood said when his wife told him. Her old landlord, who she called right away, offered her an apartment so new she won't have to fix it up. And a nice park is nearby, but it is not as lovely as Boston Common, where not long ago Bernard went back for a second visit. She was hoping to see the squirrels again. Once she moves back to Lowell, she won't go into Boston as much as she does now when traveling by T is cheap and easy. Her son, who has loved the museums and the basketball games, says he'll be back every weekend. She thinks their visits will be less frequent. Every couple of months maybe. So she and her husband went walking through the park until they found the big tree. They stood watching. But there were no squirrels. The family that was running back and forth a month or so before, racing with nuts for the nest hole, was just one of those things, she said. She was lucky to see it and lucky that it happened when it did. |