|

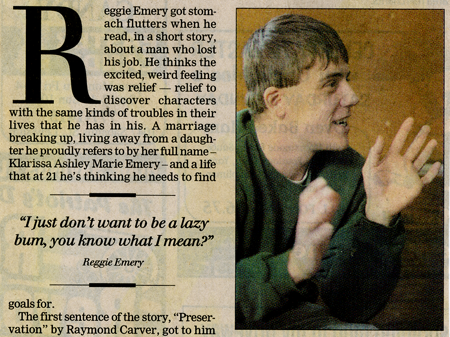

| A novel approach A special "book club" for Maine lawbreakers is changing lives. Sun Journal LEWISTON, Maine Sunday, April 15, 2001 Reggie Emery got stomach flutters when he read, in a short story, about a man who lost his job. He thinks the excited, weird feeling was relief - relief to discover characters with the same kinds of troubles in their lives that he has in his. A marriage breaking up, living away from a daughter he proudly refers to by her full name - Klarissa Ashley Marie Emery - and a life that at 21 he's thinking he needs to find goals for. The first sentence of the story, "Preservation" by Raymond Carver, got to him so much that he underlined the word "terminated." Then he wrote the word "job" over it so the passage would seem even closer to his own life. "Sandy's husband had been on the sofa ever since he'd been terminated three months ago," it said. That's what happened to Emery five months ago. He'd already gone to jail for 10 days for yanking the phone cord out of the wall when he was fighting with his wife. Then he broke his leg and lost his job doing yard work for his grandfather. The man in the story just sat on the couch. He didn't even do things with his old lady, said Emery. The man was the kind of person Emery didn't want to be. "I just don't want to be a lazy bum, you know what I mean?" he said. It's been about a month since he started going to a book discussion group every other week because his probation officer told him to. He likes it so much that when he finishes one story, he goes on to the next one, no matter what. He's read three of Ernest Hemingway's and four by Carver, whom he prefers because the stories are longer and more detailed. When Carver's "Fever" came up at a recent Tuesday afternoon book meeting, everyone talked about art teachers at first, because the story is about an art teacher who was left alone with two children after his wife ran off to California with another man. One guy said most of his art teachers were snooty. Another had teachers who were like 1960s flower children. Emery said his were outgoing. The topic of having a woman leave came next. Most of the six men had something to say about that, as they sat in pews set up against chapel walls in a church house on Bartlett Street. "He loved her one minute and then the next he hates her for leaving him," someone said. "I thought she was kind of callous the way her attitude was." They held the books in their hands, sipped coffee from Styrofoam cups and bit into donuts they'd pulled from the box passed around by a woman from the Department of Corrections. This was their third meeting since February, when the Maine Humanities Council started the group with Corrections Department money. For years the council has been leading book discussion groups at libraries and prisons. The idea is that books help people think about their lives in ways they might not otherwise. A similar Massachusetts program has shown that when people on probation and parole talk about books in groups, their rates of committing more crimes drop. Last year Maine's Corrections Department agreed to offer the five-class discussion series to people assigned to probation offices in Auburn, Biddeford, Bangor and Hallowell. Jeffrey Aronson, the former University of Vermont professor who leads the discussions, told the men they were like college students. The way they've been talking at their meetings is exactly the way people talk in those classes. He thought he'd say something just in case they're curious to know what college is like. It is much different since the first time they got together. Few people talked then. Now the conversation comes easy. The men have impressed him with their interest. He tells them to link the stories to their lives and he tries to go over all the different parts of the story. "He seems like a good guy doesn't he?" Aronson said of Carlyle, the art teacher in the story. "So why did she leave?" A man with tattoos on his arms, who said he'd spent time in a Massachusetts penitentiary, figured Carlyle's wife just wanted to be free. The mother of the man's daughter seemed to want the same thing. When he was in prison, she wrote to him and said that when he was out, it would be his turn to look after the daughter. "So this is a situation you can understand," Aronson said. "So the fact that Eileen up and ran, that makes sense to you." The daughter of the man with tattoos misses her mother and has bad dreams about it sometimes. "I can see those two little kids - if she doesn't come back to them - growing up like that," he said about the children in the story. Emery thought about his daughter, too. "If your kids aren't happy, you sure as hell ain't going to be happy," he said. He's noticed his own daughter treats him differently now that he's splitting up with her mother. What about the affair the art teacher was having with a secretary? A red-haired man with an assault charge said he had a brief romance himself after his wife left him. He knew it wouldn't last, but he needed to recover from his marriage first. Maybe that's what the art teacher was doing with the secretary - seeking comfort. Emery, who got married when he was 17, listened. When he was in school in Lisbon, everyone considered him a geek. Now in Lewiston it's different. The experiences of other guys in the book group are interesting. They're older than he is. They know a lot. Sometimes the stories are so much like Emery's life that when the parallels strike him, he talks. Hemingway's "The End of Something" was about a man who was breaking up with a woman because being with her wasn't fun anymore. It was also about how the woman, Majorie, loved to go fishing with her boyfriend, Nick. "What's it like to be with someone who likes to do the same thing?" Aronson said. "It's awesome. You don't fight, you don't argue," Emery said. Then they talked about the way Nick was annoyed by how well Marjorie knew everything he'd taught her. "She's number one in everything. I've had that happen," he said. He was thinking about the breakup with his wife. They'd promised each other they'd stay together so Klarissa Ashley Marie would grow up with her biological parents. Now she's moving to Biddeford. The court date for their divorce is April 18. Reading the stories about other people breaking up has made this all go down a little easier. He can move on with his life now, he said. At the end, before the men stood up to leave, they talked about how much they liked the class. "This should be a prerequisite to marriage," the red-haired man said. The man with tattoos said he learned from the other people when they talked. "When I leave the group, I feel better after," he said. Emery couldn't get over how this is free. The books are free and so are the coffee and donuts. He doesn't get that at the domestic abuse meetings he has to pay $30 for. There, he just sits and listens to everyone talk. What with him looking around for a job, paying child support and without a place to live, it's hard to find the money for those classes even though he knows he may wind up back in jail for missing them. "I've been trying and trying and trying and it seems like everything I try to do, it just makes it worse," he said. "I don't belong in jail because I'm not that bad." Emery was concerned about the snowstorm weeks before. They'd had to cancel one of the short story classes. He mentioned it to the professor because he wanted to be sure there would be two more of these meetings, just as the original plan had called for. Aronson said he would try to make it up. To Emery the stories were like mirrors. In every one he glimpsed something else about his everyday life and he wanted a better look. They still had two by Hemingway and two by Carver left to talk about. |