|

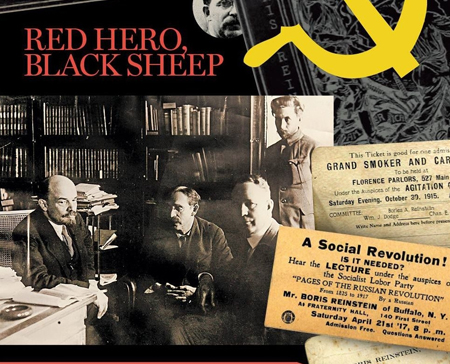

| Red Hero, black sheep Buffalo News Sunday, November 13, 2011 Section: Spotlight Page: F1 Phyllis Reinstein poured the black and white photos out of a bag and sorted them out, one by one, as if the pictures and the old secrets of the famous Cheektowaga family she married into were a card game she would get better at, the more she played. She tried matching faces among the faded, stern, smiling and blank-eyed people staring at her from the polished gleam of her dining room table. There were no names, just photo studio stamps from Buffalo and New York City, along with some in French and Russian. Plump, serious women with Victorian ruffles, grinning girls with big hair bows, a boy on a tricycle with a giant feather in his cap and a scowl. Reinstein thought she recognized the slight one with round glasses, a calm expression, beard and waved hair combed back. He seemed to be a young Boris Reinstein, a bomb-maker who became a Buffalo pharmacist, then secretary to Vladimir Lenin. "Boris, why didn't you write on the back of this?" The politically passionate man grew up in czarist Russia and advocated for communism and socialism when they were still untested political ideals. He lived in Western New York for 25 years, then, at age 51, left Cheektowaga and his obstetrician wife, Anna, to go back to Russia in 1917, the year of the revolution, and work in the new Bolshevik government. To figure him out, Phyllis Reinstein has read through letters, books, old newspapers and a box of loose papers from the old family summer house in the state park named for her wealthy, philanthropist father-in-law—Dr. Victor Reinstein, Boris' son. After more than a decade of research, she discovered disappointment, sadness and worry about Boris' departure, and politics may partly explain the reticent family he left behind. Victor, a somber doctor and lawyer who died in 1984, made lots of money capitalist-style, renting low-cost apartments and buying and selling land. The hundreds of thousands of dollars and acres of land he left for parks and libraries has made Reinstein one of the most famous names in Cheektowaga, from Stiglmeier Park with its deer and ball fields on Losson Road to the Dr. Victor Reinstein Woods Nature Preserve state park, with its prized old growth forest and stone summer house by a pond where the family picnicked. The Anna M. Reinstein Library on Harlem Road, named for his mother, has an archive of family papers. The Julia Boyer Reinstein Library on Losson Road is named for his second wife. Honorine Drive is named for his first. * * * Phyllis Reinstein found herself surprisingly enchanted with Boris the Communist, the man who died in Moscow eight years before she wed his grandson in 1955. "He was something," she said, admiringly. "I just would have loved him." To that her husband, Robert, usually just gives her a look. Robert is one of the three children of Victor Reinstein. And while the Reinsteins didn't tell her much about Boris, Phyllis discovered the fiery speaker still loudly making his points in century-old papers. A reporter recorded this indignant reaction in 1906 after he got out of jail for speaking at the corner of Main and Mohawk streets in Buffalo without a permit: "We expect this in Czarist Russia, but America is supposed to be a land of liberty, yet in Buffalo, an American city, they drag me and other speakers of the Socialist Labor Party to the police station," according to the Buffalonian.com transcription of a Courier story. The historical record of Reinstein is profuse, from a mention in the book about the 1917 revolution, "Ten Days That Shook the World," by Communist-sympathizing American journalist John Reed to more books, pamphlets, news stories, speeches and this handwritten essay in the Reinstein library collection. "[I]t is the historic mission of the proletariat—the propertyless wage-earning class—to establish this new social order by transforming all means of production, distribution and exchange into joint property of the people," Boris Reinstein wrote on a few pages titled "A Timely Lesson From History." "I don't know if this guy ever slept when you see what there is about him," Phyllis said. Now, after 56 years as a Mrs. Reinstein, she thinks the story of Boris may explain why her father-in-law Victor smiled so rarely. "He was upset with his father because he left his mother," she said of Victor. To look back now, the family's caution was also rooted in McCarthy-era blacklists and trials. If she had known, Phyllis may have hesitated to get married at 21 to the young Robert Reinstein she met during high school. "I was such a goody-two-shoes." "I was brought up in this Catholic family, and Communism in Russia—that was all terrible stuff," she said. When they were newlyweds, Robert began a career as a state trooper and the couple lived around the state until Victor feigned a heart attack to get his son home to help manage the family real estate business. Phyllis didn't hear of Boris until 1963, when she met Victor's fun-loving sister Nadina Reinstein Kavinoky, a doctor in California. Once Phyllis acted on her suggestion to "Ask Victor about his father," mentioning "Boris" in casual conversation. Victor looked at her and said nothing. "So I learned," said Phyllis. "I didn't bring him up again." She let it go. And stayed curious. "It just kind of sparked a light in my head," she said. By the 1990s, her two sons had started careers as police officers, she had retired from her quality-control job at St. Joseph Hospital, Victor was dead, and she had more time and nerve. Phyllis took a seminar on genealogy and used a terse clue from her husband, who had no interest in his grandfather: Boris worked for Lenin. Her husband preferred Anna, the grandmother who raised him after delivering him on the dining room table during a snowstorm. But as the discoveries piled up, the rest of the family got inspired, too: From her police officer son Robert, who visited Boris' gravestone in Moscow to her investment adviser grandson. "You just want to keep the streak going," said Ronald Reinstein, one of the Financial Guys in Williamsville. * * * Like a kind of Communist Forrest Gump, Boris had a knack for being close to power and news. He wasn't famous like Trotsky, Lenin and Stalin. He knew and served them. From 1917 to his death in 1947 at age 81, letters home and even Senate Committee testimony chronicle his posts. From minister of propaganda and labor to adviser and secretary to Lenin and on: He was an organizer of the Comintern, the Communist International organization founded in 1919 after the revolution to spread communism worldwide. And, later in life, English editor of Sovietland magazine. Headlines in now-defunct local papers tried to keep track. "Buffalo Druggist Now One of 'Red' Rulers in Moscow," in a 1922 Courier story. "Will Revoke Citizenship of Boris Reinstein," the 1923 Times. "Wife Confident Reinstein Still Serving Russia: Latest Word Received More Than a Year Ago," the Courier in 1943. At an empty table near the back rooms of the Reinstein archive at the Anna Reinstein Library in Cheektowaga one afternoon, Phyllis studied a yellowed edition of the French newspaper L'Eclair from Saturday, July 5, 1890. It revealed Anna and Boris' rebellious beginnings. The headline called them "Nihilistes"—a derogatory term for radicals. They were arrested as part of a group that plotted, and failed, to assassinate Czar Alexander III, who eventually died of natural causes. Boris would later explain in a 1922 Courier story that he and others experimented with making bombs in a forest outside Paris when one blew up prematurely. At the time Anna and Boris were 24 and married with a 2-year-old daughter. They'd met at university in Bern, Switzerland. She was a doctor and he, according to the Courier story, focused on chemistry and revolution. The couple's life was shaped by 19th century political currents: At the time, young Russian Jews had limits on where they could live and study, and some turned to radical politics, said Steven Zipperstein, professor of Jewish History and Culture at Stanford University. "Radical circles in Russia are the one place that feels like a neutral zone for Jews," said Zipperstein. "It's a place where actually you can join the larger Russian society, a place where young Jewish men and women can consort with non-Jews." Boris went to prison; Anna was released and left for the United States with Nadina in 1891, choosing Buffalo, the family story goes, for its high concentration of Poles. "I would love to know what she did when she got to Buffalo," said Phyllis. "She didn't know anyone there." Boris joined her in Buffalo in 1892 after he got out of prison, where, the Courier story reported, he said, "I studied Marx's works in French and tried to follow the international socialist movements as much as I could." He went on to say he abandoned violence because in the U.S. "people have conquered sufficient elementary rights and liberties to be able to educate and organize the proletariat for the social revolution." He eventually got a degree in pharmacy from the University of Buffalo. * * * "It's really a fascinating story," said Daemen College professor Andrew Wise, who spent about 40 hours reading through the archive at the Cheektowaga library this past year. A specialist in Russian history, Wise was intrigued by the socialist-capitalist contrasts in Anna's and Boris's Buffalo lives: They had a pharmacy and medical practice, bought a house on Bellevue Avenue in Cheektowaga and organized for the Socialist Labor Party. In 1916, Boris even ran as its candidate for lieutenant governor. "They were doing pretty well," said Wise, "yet they are opposing the system that allows them to do pretty well." From the archives and other research he pieced together a chronology of their lives. Last month he presented his paper, "An American Bolshevik: The Evolution of Boris Reinstein's Political Ideology," to the state association of European Historians, along with this 1893 speech Anna gave to several hundred local Poles: "Workers, you must organize into unions and stand ready to resist the tsars! No one will help you unless you help yourselves. Each capitalist works for the other while the laborer starves. You should hate capitalists like a mad dog and not make a jackass out of yourselves at election time. The Socialist (Labor) Party is the one that will help you." The Cheektowaga archives also reveal loving letters and a family who missed the ever-traveling socialist-organizer Boris. One postcard to him, with an image of Masten Park High School, had a short, plaintive note: "Why don't you write me a letter? I did not write you a letter because you only wrote me a partial. It is tit for tat. Victor." Nadina writes in teasing riddles the news that she had fallen in love. "Dear daddy, Well where shall I begin? I always knew something would happen when I became twenty I felt sure I'd catch something but I didn't know what it would be—typhoid, pneumonia, measles or be wounded by cupid's arrow I'm awfully sorry that you are not here, but we will try to make the best of it." In 1917, when news of the revolution broke, Boris could not resist returning to Russia. Anna told a reporter that he asked her to go with him, but she didn't elaborate. In the 1922 Courier account, Boris focused on politics: "The fall of czar came as a shock to Reinstein." After days of puzzling, he said he decided to go "preach the doctrine of the industrial state." By coincidence, the story said, Boris was on the same ship as a "shabbily dressed, longhaired, bearded" Leon Trotsky, who would be a "commissar" and leader in the new government. "It was difficult for them to talk much together, for Trotsky knew little English and Reinstein had completely forgotten his Russian. But with the French that both had learned in Paris and the occasional searching through the dictionary, they were able to form a friendship which has endured through five years of storm and strife in the revolutionary councils of Russia." Boris' career took off. In "Ten Days That Shook the World," about the 1917 revolution John Reed quotes Reinstein, as a "delegate of the American Socialist Party": "A great idea has triumphed. The West, and America, expect from Russia, from the Russian proletariat, something tremendous." Then Reed describes a winter evening procession and celebration of that promise: "From somewhere torches appeared, blazing orange in the night, a thousand times reflected in the facets of the ice between crowds that stood in astonished silence. 'Long Live the Revolutionary Army! Long Live the Red Guard! Long live the Peasants!'" * * * To hear some of the details of the Reinstein story, it seems obvious Boris "was an idealist," said Joshua Rubenstein, author of "Leon Trotsky, a Revolutionary Life." "One can't help but think that he was stirred and disillusioned." When Reed's wife, Louise Bryant, testified in a 1919 Senate committee hearing about the new Bolshevik government, she said Reed worked for a time in the Bureau of International Revolutionary Propaganda, which Reinstein headed. "Mr. Reinstein is now the secretary of Lenin," she told the senators. Bryant also sent updates about Boris to Cheektowaga: "He was well and happy in his work but lonesome for his family. He often spoke of you both and longed to see you." Reed died of typhus the next year at 32; an old photo shows Reinstein speaking at his Moscow funeral. Boris' letters home and reports from friends who visited suggest his life was deprived of material comfort, but not love. In 1921, a friend wrote that his new wife was "quite an attractive woman in every way" and "going to have a baby very soon now." There was a long list of requests—from a Madame Butterfly record for his Gramophone to a suit of warm underwear and soda crackers, "which can be used in place of bread." While Anna told a local reporter "with comfortable reassurance" that Boris had not remarried, Nadina was appalled by the truth. "To say the least, the true state of affairs is disgusting to me," she wrote in a letter Wise found. Reinstein, who eventually had his U.S. citizenship revoked, managed to sneak back to the U.S. in the summer of 1922. A letter in the archives shows how tycoon Armand Hammer, whose Russian business deals Boris helped arrange, wrote about a New York rendezvous with Anna at the Hotel Ansonia that year. "There is so much I would like to tell you and it is of such a nature that I would much prefer seeing you than attempting to write you about it," Hammer wrote, mysteriously. That trip, Boris' last to the U.S., included a stop to speak at a clandestine Communist Party meeting in Michigan. "Federal agents raided the meeting, arresting 20 men and women, but did not catch Reinstein," said a Buffalo Courier article from November 1922. Anna told a Courier reporter in 1943, "Boris did make a brief trip here to say, ‘hello’ to his family and look around, but he returned almost immediately to Russia, where he has remained ever since." When Joseph Stalin took over after Lenin's death in 1924, some of his rivals were banished or executed. Boris survived. Letters toward the end of his life, after World War II, report work on his memoirs and intestinal troubles that led to letters about his need for shipments of powdered milk, vitamins and canned baby food. About a year after writing Anna for "a couple hundred dollars," he died in 1947 and was buried in the same elite Novodevichy cemetery in Moscow where Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev later was buried. Anna died a year later. Her legacy of delivering babies for people in need and under any circumstance grew more famous than her politics. A mural of local history at an M&T Bank office at the Thruway Plaza shows her in a dress, using a railroad handcar to get to a Gypsy encampment for a breech delivery that she was paid for with two chickens, said Phyllis. After so many years, the family story is like a novel she hasn't finished yet. She wonders what happened between Boris and Anna before he left. "I think she loved him ‘til the very end," Phyllis said. "I think she went to the grave with a lot of secrets." The family story and the adventure of it has become a part of Phyllis and she wants to discover more. She says she used to be the sort who was content doing her job and raising her family, but Boris turned her all around. Now she's a curious person, and she isn't finished yet. |