|

| In the saddle on life's tricky ride

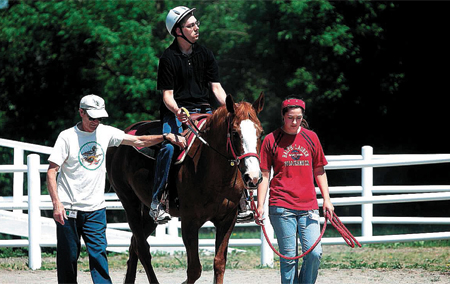

Gathering Story Series BUFFALO NEWS Monday, June 7, 2010 Section: Local News Page: B1 It took four people to gently guide Victor Hale Schramm out of his motorized wheelchair so he could stretch and settle onto Stoney, a stocky, grayish-brown horse with long lashes who one volunteer imagines would smoke cigars if he could. From up high, Schramm's head leaned toward one side as he held the reins while the horse neighed. He likes to take in the scene at the therapeutic horse riding center in Aurora, where people with handicaps learn to ride. It is named Lothlorien, after the magic forest refuge in the "Lord of the Rings" stories, but the scene of the stable and the horses in the pasture makes Schramm feel like he's in a Western movie. Being here makes life seem normal again for Schramm, 46. "It makes me feel able," he said in the electronic voice that speaks what he types on the keyboard attached to his chair. Of the process that led Schramm to fit his shiny black boots in the stirrups, his instructor Michele Kray observed, "We think he's going to fall, but he knows what he's doing." On this afternoon, it was hot enough to make Schramm uncomfortable. The sun beat down at 80 degrees. The day had a disconnected, out-of-sync beginning. His van service had come too early. He had been stuck waiting for an hour or so as the men from the Finger Lakes group homes finished lessons. Disabilities vary. Instructors at Lothlorien have different ways of helping people relax, use stomach muscles to hold balance and become confident in their skill. When everything comes together, riding lessons lead to more subtle adventures. Reins have red, blue, green and yellow patches, so it's easy to tell a person where to hold. For fun, instructors set up games and puzzles. For the day's first lessons, the men outside rode from one barrel to the next hooking and unhooking toy fish from poles. Until it was his turn, Schramm, aide Carol Sacash and his panting black dog, Tide, kept cool in the office of the center's ranch house. On the wall was a framed colored-pencil portrait that a volunteer drew of Blossom, a friendly-looking chestnut horse who had died after a long career. There were bits of hay stuck all over the dark carpet and a picture-window view of the pastures enclosed by white pole fences. Schramm visits twice a week. Even if he decides not to ride, he socializes. He is "Hal" to the people at Lothlorien, who wait without impatience as he carefully types replies in conversation. About 20 years ago, he said, he resisted his mother when she suggested that he come here. "She had to talk me into it," he said. "Now I'm grateful that she did." Horse manager Jennifer Stossel-Anderson listened. She learned in high school that these riding sessions can make a big difference in a person's life. A classmate with a disability explained that they made him feel like everyone else. "He felt like he fit in," she said. Outside, at the corral, the men from the Finger Lakes ended their lessons with victory laps. They rode, smiling, hands free. With arms stretched out like airplane wings and hands fluttering, it was as if, in a moment of self-revelation, they were saying, "Wow, I'm doing this! I'm not hanging on!" Riders have volunteers nearby as a precaution. For one lesson with four people, 16 may team up in trios -- leading the horse and walking on either side. In a year's time, about 200 of them work with about 160 riders. Founded in 1983 with foundation money, Lothlorien is one of about 800 members of the North American Riding for the Handicapped Association. Riders, from 3-year-olds to grown-ups, have a range of disabilities. Mental handicaps. Cerebral palsy. Traumatic brain injury and body damage, such as from the car crash in which Schramm was involved at age 19. Schramm had just graduated from high school in Pittsburgh and had taken his father's Corvette for a ride. A drunken driver slammed into him as he waited for the light to change. He was in a coma for five months. When he came out of it, he had to learn how to live in a wheelchair. Kray, Schramm's instructor, has worked with him for four years and knows his routine. He likes to joke. To warm up and stretch before he gets on the horse, she bends, and he lifts up his leg to "kick" her -- tap, actually -- in the rear end. She could tell that Schramm was looser on this day. He was letting his muscles relax, which made for a happier horse and a better ride. He had the control he needed to regain his balance after she saw him lose it. Schramm and Stoney stepped easily through the arched pattern paths she made by setting white plastic markers in the dirt. "Turn to the right and bring Stoney back to the pattern again," Kray said. She earned certification as an instructor after beginning as a volunteer. By working with Schramm, she found she has become a more patient person and has learned how to explain things better. "Jiggle your reins and ask him to go slow," she said. Then Schramm surprised her. He sat straight in the saddle, instead of leaning back as he sometimes does. He pulled the reins toward his hips instead of lifting them high. What resulted was a perfect cue. For about five steps, Stoney walked backward as gracefully as he walks forward. Everyone noticed. "Great job, Hal!" Kray said. "What a cowboy!" someone said. For a horizontal high-five, a volunteer pressed his palm to Schramm's. He'd had enough. He was too tired for a full lesson. Schramm got back in his chair, and he pointed to Stoney. He wanted to say goodbye. The horse was led to him, and right away, Stoney bent down close for their usual nuzzle. Then the horse did it again. Pressing his nose for a second time into the sideways tilt of Schramm's cheek. Like a kiss. |